If you’ve ever struggled to lose weight, you’ve probably blamed your metabolism.

Most people do.

But here’s the truth — and it may surprise you:

The only time your metabolism is actually “broken” is when you’re dead.

As long as you’re alive, your metabolism is running. It never shuts off, never hits zero, and never stops burning.

So why does it feel like metabolism is the obstacle?

Because “metabolism” has become one of the most misunderstood and misused words in the entire fitness industry — and the confusion has misled millions of people into believing something that simply isn’t true.

Let’s set the record straight.

The GLP-1 Effect: What It Actually Reveals

Over the past few years, GLP-1 medications (Ozempic, Wegovy, Mounjaro) delivered something the weight-loss world hasn’t seen before:

consistent, dramatic fat loss — even in people who believed their metabolism was “the problem.”

consistent, dramatic fat loss — even in people who believed their metabolism was “the problem.”

Here’s the part most people misunderstand:

These drugs don’t increase — or even maintain — metabolic rate.

They actually lower it — not because of the drug itself, but because they sharply reduce calorie intake. That reduction creates a large calorie deficit, which leads to weight loss. And that weight loss triggers adaptive thermogenesis, which naturally lowers resting metabolic rate (RMR), just as it does with any method of losing weight.

So people aren’t losing weight because their metabolism speeds up.

They’re losing weight because — for the first time — they’re consistently eating fewer calories than they burn.

GLP-1s revealed something the science has shown for decades:

Most people aren’t struggling because of metabolic slowdown … they’re struggling because of energy mismatch — calorie intake exceeds calorie output more often than they realize.

Metabolic Mythology: How We Got So Confused

“Slow metabolism” gets blamed for everything — from stubborn fat to low energy to failed diets.

The problem?

Even many professionals can’t accurately explain what metabolism is. Instead, misinformation spreads:

- sensational claims

- fake fixes

- “miracle” foods

- pseudoscience disguised as expertise

Companies jump in with products to sell. Influencers amplify the noise. The public absorbs it as truth.

But evidence paints a very different picture.

Most People Focus on the Wrong Piece of Metabolism

When people try to “boost metabolism,” they almost always mean increasing resting metabolic rate (RMR) — the calories your body burns at rest.

RMR matters. But this often-overlooked fact changes the entire conversation:

RMR is only one of four metabolic engines — and it's the least modifiable.1,2

Your daily calorie burn comes from:

- Resting metabolic rate (RMR)

- Non-exercise movement/activity

- Exercise (formal/planned activity)

- The thermic effect of food (digesting food)

RMR accounts for about 60–65% of total daily expenditure, but it’s largely determined by your height, weight, age, sex, and body composition — not by hacks, supplements, or “fat-burning” foods.1,2

And here’s the irony:

Even though RMR is the largest contributor to your total daily calorie burn, it’s also the least responsive to attempts to increase it. Aside from gaining significant amounts of body mass or building substantial muscle — both of which raise RMR only modestly — most interventions barely move it.The other metabolic engines, especially daily activity and planned exercise, are far more modifiable and have a much bigger impact on total daily energy expenditure. This is why focusing exclusively on “boosting RMR” leads so many people in the wrong direction.

If this kind of myth-busting clarity is helping, you’ll love what comes next.

Every week I break down the research on metabolism, weight regulation, and long-term fat loss — without the noise, hype, or gimmicks.

👉 Join the Body by Ry™ Breakdown — free weekly insights delivered to your inbox.

No Spam. Unsubscribe anytime.

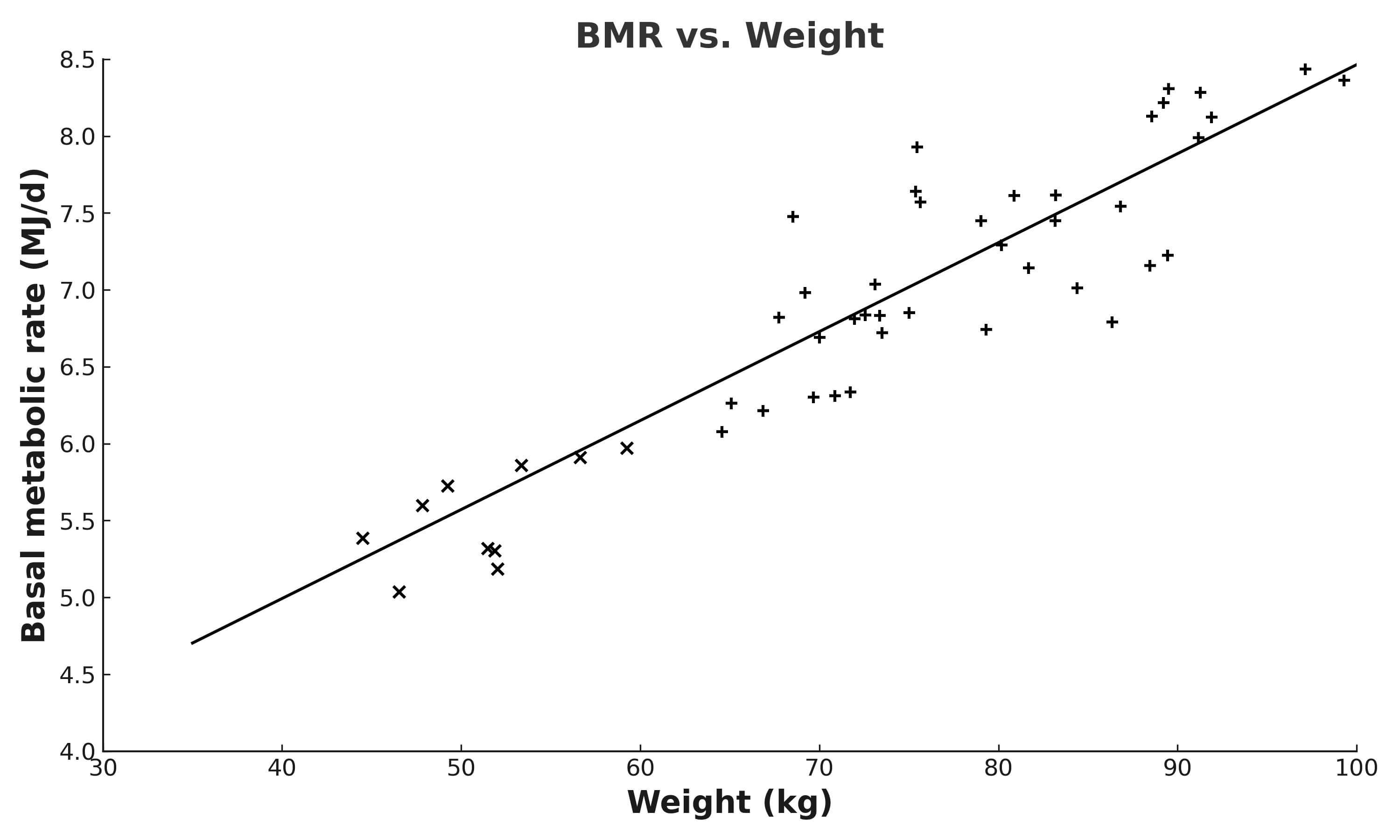

Heavier People Don't Have Slower Metabolisms — They Have Faster Ones

This contradicts what most people believe, but it’s true:

Heavier bodies burn more energy — both at rest and during movement.

More mass → more tissue to fuel → more calories burned.

Lean, lighter bodies burn fewer calories — not because their metabolism is “broken,” but because they’re smaller.

And research consistently shows:

Overweight and obese individuals usually have higher RMR than lean individuals — not lower.3

To visualize this relationship, look at the data below. Each point represents an individual, and the upward trend shows a clear pattern: as body weight increases, resting metabolic rate increases too.

Figure 1. Resting metabolic rate rises as body weight increases. Heavier individuals consistently display higher RMR because they have more total tissue to energize, not because their metabolism is “slow.”

Figure 1. Resting metabolic rate rises as body weight increases. Heavier individuals consistently display higher RMR because they have more total tissue to energize, not because their metabolism is “slow.”Even more surprising?

A large 10-year study found that people:4

- With significantly lower RMR than predicted for their size did not gain more weight over time.

- With significantly higher RMR than predicted for their size did not gain less.

RMR simply didn’t predict future weight gain.

Why?

Because the body adapts.

- People who are less active may adaptively develop higher RMR, and they tend to eat more than they burn.

- People who are more active may adaptively develop lower RMR, and tend to match daily calorie intake to output.

Across time, the playing field levels out.

So Why Do Some People Gain Weight More Easily?

Not because RMR is too low.

Not because metabolism is “broken.”

Weight gain is driven primarily by cumulative calorie surplus — whether from consistent patterns or episodic overeating — not daily swings, but long-term patterns.

And why some people are more vulnerable to ending up in that surplus is complex:

- genetics

- hunger/satiety signaling

- food access

- obesogenic environments

- low activity

- high stress

- insufficient sleep

- poor self-regulation

Metabolism plays a role — but not the starring role people assume.

"But What About People With Really Slow Metabolism?"

This idea needs correction.

Individuals on the reality TV shows Survivor, Alone, The Biggest Loser, and others undergoing extreme fasting did not necessarily start with unusually slow RMR.

The real point is this:

Their RMR dropped precipitously during weight loss — yet they still lost extraordinary amounts of weight.

Angus Barbieri — the world record holder for the longest fast — fasted 382 days.5

His RMR plummeted.

He still lost 276 pounds.

Figure 2. Angus Barbieri before and after his 382-day medically supervised fast — an extreme case demonstrating that even large reductions in RMR cannot prevent weight loss when calorie intake remains below calorie expenditure.

Figure 2. Angus Barbieri before and after his 382-day medically supervised fast — an extreme case demonstrating that even large reductions in RMR cannot prevent weight loss when calorie intake remains below calorie expenditure.The Biggest Loser contestants saw their RMR fall by hundreds of calories.6,7

Yet they still lost 128 lbs (on average), and half maintained >13% weight loss six years later through calorie control and consistent exercise.

And here’s what’s even more remarkable:

The contestants who kept the most weight off weren’t the ones whose metabolism “recovered” the most — they were the ones who consistently managed calorie intake and exercised the most.

Data showed that differences in calorie intake and activity explained 93% of the variation in long-term weight loss, even though some contestants had far greater drops in RMR than others.6

In other words, a reduced RMR wasn’t the deciding factor. Behavior was.

A suppressed RMR does not prevent weight loss — and it does not force weight regain.

If calorie intake matches calorie output during weight loss maintenance, weight stability holds.

What Actually Matters Most?

RMR is not the lever most people think it is.

The strongest predictors of long-term weight control are:

✔ consistency of calorie intake

✔ habits that support hunger regulation

✔ self-discipline and awareness around food

✔ a sustainable food environment

✔ total daily activity

✔ exercise (any type you can sustain)

✔ general daily movement (NEAT)

✔ regular sleep routines that support 7–8 hours nightly

✔ habits that support hunger regulation

✔ self-discipline and awareness around food

✔ a sustainable food environment

✔ total daily activity

✔ exercise (any type you can sustain)

✔ general daily movement (NEAT)

✔ regular sleep routines that support 7–8 hours nightly

Metabolism matters — but it’s not the master variable.

So... Is Metabolism Really The Problem?

Not exactly.

Your metabolism isn’t broken.

It isn’t sabotaging you.

And it isn’t the hidden villain many people assume.

It isn’t sabotaging you.

And it isn’t the hidden villain many people assume.

But here’s the nuance:

Metabolism can become an issue — especially during and after weight loss — but its influence has been overstated and misunderstood.

RMR and total daily energy expenditure shift as your weight changes. Appetite and satiety adjust. So during and after weight loss, metabolism must be intentionally supported and optimized to prevent weight drifting back toward your previous weight.

So no — metabolism isn’t the problem.

But it is part of the equation.

And in the articles that follow, I’ll break down the most evidence-based strategies to optimize your metabolism:

- during weight loss (to maintain steady progress), and

- after weight loss (to prevent regression)

Because your biology isn’t broken.

You just need the right blueprint — and that’s what’s coming next.

Want weekly science-backed breakdowns like this?

Join the Body by Ry™ Breakdown — free, practical, and straight to your inbox.

Join the Body by Ry™ Breakdown — free, practical, and straight to your inbox.

No Spam. Unsubscribe anytime.

If you found this breakdown helpful and want the complete science of fat loss explained in a way that finally makes sense, you’ll love my book Burned™.

It teaches you the exact biology behind weight gain, metabolic adaptation, appetite, plateaus, fat loss, and long-term weight maintenance — without the fads, myths, or gimmicks.

👉 Get your copy of Burned here → Buy Burned™

(and start working with your biology instead of against it).

(and start working with your biology instead of against it).

References

3. https://www.researchgate.net/publication/10887601_Energy_requirements_of_women_of_reproductive_age